I mentioned in my last post that a particular book has been influential in helping me understand how prayer and spiritual practices affect the brain. While I have consumed a dozen or so books and audio programs on meditation and prayer, the one that has had the most impact on its own is definitely How God Changes Your Brain (2009) by Andrew Newberg and Mark Robert Waldman.

This book gave me a picture of what happens in the brain when people pray, meditate, and practice other spiritual activities. The authors describe the parts of the brain and how they are affected, and what that means. They reviewed how people perceive God within various groups and how brain development is connected with those views. They even discussed the activities that are most beneficial for brain health and how to create a meditative routine that works best for you.

Before I go on, I want to say quickly that this discussion—including all the other posts in this series—is about prayer and meditation’s affect on the person praying. I am not touching at all on whether prayer influences the world around us or influences God. That is the subject of an entirely different conversation.

Also, I think it would be helpful at this point to define some terms. The spiritual tradition of my childhood and of many other people I know were skeptical at best—and aggressively averse at worst—when it came to the subject of “meditation.” The general fear at play was that it was believed meditation was exclusively for Eastern religion, and therefore opposed to God, and it involved completely emptying one’s mind, which “of course” opened the way for every passing demon to make itself at home.

Here’s why I think that’s the wrong way to think about it. Newberg and Waldman define meditation this way (and I agree with them): “Meditation, however, is commonly defined as a contemplative reflection or mental exercise designed to bring about a heightened level of spiritual awareness, trigger a spiritual or religious experience, or train the mind in a specific way” (Newberg & Waldman, 2009, p. 48). Many traditions, including Catholic Christian, Orthodox Christian, and probably every other type of Christian participates in practices that fit that description.

Prayer, then, is not a distinct activity from meditation, but rather it is a specific type of meditation that involves words in a discussion format with God. The authors specify making a request to a deity, but I believe that to be too narrow a definition for prayer. In fact, Richard Foster’s book Prayer: Finding the Heart’s True Home discusses 21 distinct types of prayer, and I don’t think he exhausted the possibilities. In fact, he has chapters on “prayer of rest,” contemplative prayer, and meditative prayer, all of which could be labeled meditation rather than prayer depending on who you talk to.

The point is the dividing lines are not clear, and whether you define prayer as a type of meditation (probably more technically correct) or meditation as a type of prayer (possibly more practical for Christians comfortable with prayer at this point) the outcome is the same: meditation is what you make it. If you intend to reach out to God through meditation, God will meet you there. In fact, removing the biases of my childhood, I have become convinced that it’s an essential piece of what God has intended for his people all along.*

With those things in mind, here are some of the highlights from the book:

“Activities involving meditation and intensive prayer permanently strengthen neural functioning in specific parts of the brain that are involved with lowering anxiety and depression, enhancing social awareness and empathy, and improving cognitive and intellectual functioning. The neural circuits activated by meditation buffer you from the deleterious effects of aging and stress and give you better control over your emotions. At the very least, such practices help you remain calm, serene, peaceful, and alert. And for nearly everyone, it gives you a positive and optimistic outlook on life” (Newberg & Waldman, 2009, pp. 149-150).

That’s a pretty good list of benefits, if I’ve ever heard one. Interestingly, though, short prayers, or the vast majority of prayer activities I have normally experienced don’t fall into that category. Here is what they have to say about those:

“Brief prayer, however, has not yet been shown to have a direct effect upon cognition, and it even appears to increase depression in older individuals who are not religiously affiliated. However, when prayer is incorporated into longer forms of intense meditation, or practiced within the context of weekly religious activity, many health benefits have been found, including greater length of life. Prayer is also associated with a sense of connection to others, but the reason it may have little effect on cognition has to do with the length of time it is performed. Prayer is generally conducted only a few minutes at a time, and we believe that it is the intense, ongoing focus on a specific object, goal, or idea that stimulates the cognitive circuits in the brain” (Newberg & Waldman, 2009, pp. 28).

Spending a significant amount of time focused solely on prayer and meditation, neurologically speaking, is what counts. Saying a blessing before a meal might be meaningful in other ways, but it doesn’t change your brain.

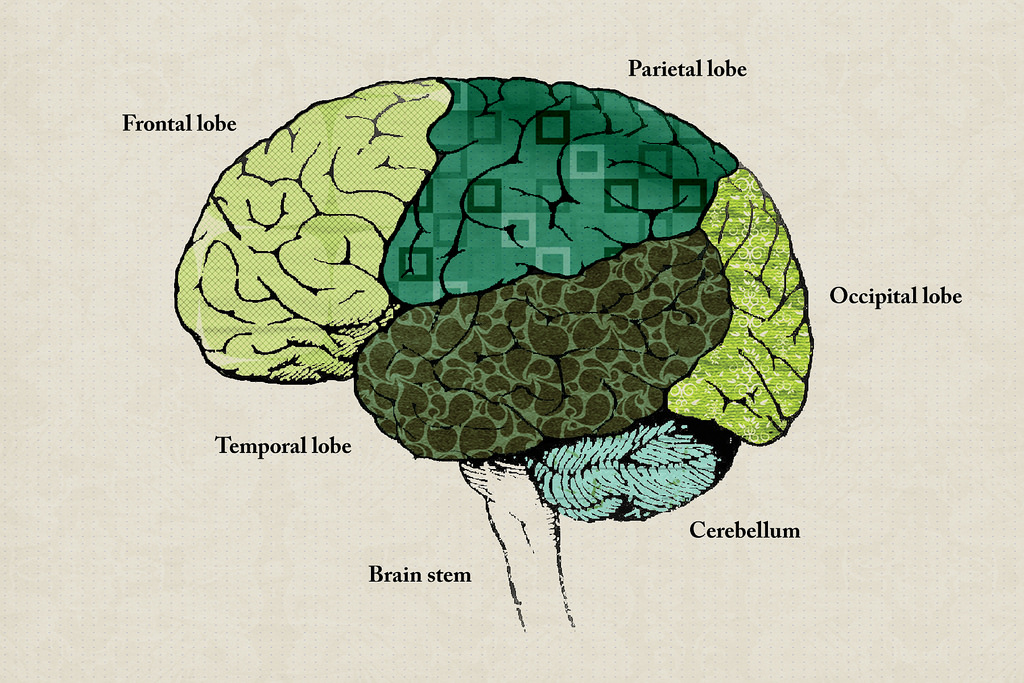

Bear with me as we walk through the relevant parts of the brain and what is going on there during prayer and meditation:

The occipital-parietal circuit “identifies God as an object that exists in the world.”

The parietal-frontal circuit “establishes a relationship between the two objects known as ‘you’ and ‘God.’ It places God in space and allows you to experience God’s presence. If you decrease activity in your parietal lobe through meditation or intense prayer, the boundaries between you and God dissolve. You feel a sense of unity with the object of your contemplation and your spiritual beliefs.”

The frontal lobe “creates and integrates all of your ideas about God—positive and negative—including the logic you use to evaluate your religious and spiritual beliefs. It predicts your future in relationship to God and attempts to intellectually answer all the ‘why, what, and where’ questions raised in spiritual issues.”

The thalamus “gives emotional meaning to your concepts of God. The thalamus gives you a holistic sense of the world and appears to be the key organ that makes God feel objectively real.”

The amygdala: “When overly stimulated, the amygdala creates the emotional impression of a frightening, [authoritarian], and punitive God, and it suppresses the frontal lobe’s ability to logically think about God.”

The striatum “inhibits activity in the amygdala, allowing you to feel safe in the presence of God, or of whatever object or concept you are contemplating.”

The anterior cingulate “allows you to experience God as loving and compassionate. It decreases religious anxiety, guilt, fear, and anger by suppressing activity in the amygdala.”

(Newberg and Waldman, 2009, pp. 43-44)

Six of the seven above neural circuits or organs relate to knowing, experiencing, and trusting God more deeply. These six are all strengthened significantly through meditation. The seventh, the amygdala, is the one that creates a mental divide between us and God, and its activity is suppressed by meditation. Not only do these effects happen during meditation, but they happen cumulatively even when participating in other activities when a person has developed a daily, habitual meditation discipline.

Not only do they change or develop your perception of God, but they make you more like those things as well. Meditation creates love, compassion, patience, peace, joy, and hope in you, without necessarily meditating on those specific ideas. Even more, meditating on divine attributes or gifts of the Spirit, like love, joy, peace, hope, eternity, trinity, compassion all serve to strengthen the health of the brain and create a transformative effect on the thought life and behavior of the meditator. However, meditating on fear or anger literally damages circuits in the brain, causing the opposite effect of these other practices.

These nuggets of information are all fascinating in and of themselves. They are even useful, and I plan to use them as the springboard for building a discipline of prayer and meditation for myself and to share with anyone who wants to join me. But there is still more to explore.

Newberg and Waldman are not religious, and they take a completely objective approach to their research and conclusions. They answer the “what, when, and how” but cannot possibly use scientific, empirical methodology to answer “why?”

We have to fill in that cosmic gap for ourselves. For me, starting with a presupposition of a personal, compassionate, and creative God who did and does come to us to be with us in the ultimate spiritual and personal sense, I see a whole realm of providential design.

The very fact that many of these brain functions exist exclusively in human brains is an indication of the image of God.

The very fact that thinking deeply about love creates positive physical changes in the brain is an indication we were made by the God who is love.

The very fact that we can become more like Christ through prayer and meditation is an example of the possibility of being transformed through the renewal of our minds.

We were not made to be mindless. We were not made to be loveless. We were not made for violence or fear. Perfect love casts out fear, and we were made to immerse our wills, our hearts, our minds, and our souls in the vastness of divine love. We were made to let that love renew us and change us and lead us to think about love, feel love, and live love in tangible ways.

I have chosen to pursue what I consider to be a serious contemplative practice on the basis of these ideas and others. I have completed five out of eight weeks of Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction, learning to discipline my mind to focus the way I want it to. I have already begun to be transformed in tangible ways, and I have not yet transferred my practice to one of specifically Christian significance.

I have, however, begun listening to and reading several works by respected masters of Christian spirituality, like Thomas Merton, James Finley, Thomas Keating, Teresa of Avila, and more. I have begun to explore the significance of Centering Prayer, Lectio Divina, praying the Rosary, Ignatian exercises, and meditating on God.

I am still learning. I probably will always be learning, but I am ready to begin doing and being. I dream of enriching my own spiritual experience and connectedness with the Holy Spirit. I dream of being an instrument to help others access similar visions for themselves. I will continue to reflect on my experiences, somehow putting into words as best I can what cannot truly be expressed with language.

The scientific achievements of our age have made it possible to demonstrate physically what the wise and the sacred have known in other very different ways for thousands of years. I appreciate that. I gain from Newberg’s work. Now, I hope to gain from experiencing God for myself.

* There are approximately 20 direct references to meditation in the KJV Bible (and I would argue much more implied evidence for meditative practices, especially since other translations sometimes obscure things with words like “relax” or “muse,” but that is for another time). Here they are: Genesis 24:63; Joshua 1:8; Psalm 1:2; Psalm 5:1; Psalm 19:14; Psalm 49:3; Psalm 63:6; Psalm 77:12; Psalm 104:34; Psalm 119:15; Psalm 119:23; Psalm 119:48; Psalm 119:78; Psalm 119:97; Psalm 119:99; Psalm 119:148; Psalm 143:5; Isaiah 33:18; Luke 21:14; and 1 Timothy 4:15.

Share Your Thoughts